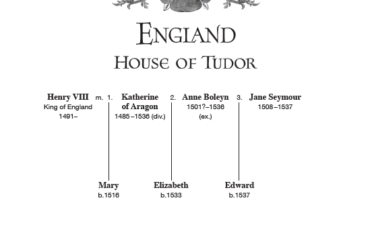

Kleve: House of La Marck

Kleve: House of La Marck

A German princess with a guilty secret.

The King is in love with a portrait, but the real Anna does not enchant him.

She must win him over. Everyone knows that Henry won’t stand for a problem queen.

But rumours of Anna’s past are rife at court – dangerous talk that could mark her downfall. Can this clever, spirited young woman reach out in friendship to the King, and gain his love forever?

The fourth of Henry’s queens. Her story.

History tells us she was never crowned.

But her tale does not end there.

1530

Anna peered through the window of the gatehouse, watching the

chariot trundling through below, enjoying the rich sensuousness of the

new silk gown she was wearing, and conscious of her parents’ expectations

of her. At fourteen, she should have learned all the domestic

graces, and to impress their guests with her virtues.

Every summer, Vater – or Duke Johann III, as his subjects knew

him – brought his wife and children here to the Schwanenburg, the

great palace that towered on a steep rocky hill, dominating the mighty

River Rhine and the fair city of Kleve. Joining them today for a short

visit, were Onkel Otho von Wylich, the genial Lord of Gennep, and

Tante Elisabeth, who never let anyone forget that she was the granddaughter

of Duke Johann I. With them would be Otho, Onkel’s bastard

son. For all the reputation of the court of Kleve for moral probity,

bastards were not unwelcome there. Anna’s paternal grandfather, Duke

Johann II, had had sixty-three of them; not for nothing had he been

nicknamed ‘the Childmaker’. He had died when Anna was six, so her

memories of him were vague, yet the living testimony to his prodigious

fertility was all around her at court and in the great houses of Kleve. It

seemed she was related to nearly everyone in the united duchies and

counties of Kleve, Mark, Jülich, Berg, Ravensberg, Zutphen and

Ravenstein, over which her father ruled.

Duke Johann was lavishly dressed as usual, welcoming his guests

as their chariot drew up at the gatehouse – dark hair sleekly cut, fringe

and beard neatly trimmed, portly figure swathed in scarlet damask.

Anna looked at him affectionately; he did love to make a show of his

magnificence. At his command, his wife and children were attired in

rich silks and adorned with gold chains. Anna stood in a row with her

younger siblings Wilhelm and Amalia, who was fondly known as Emily

in the family. Vater and Mutter had no need to remind their children to

make their obeisances, for courtesy had been drummed into them since

they had been in their cradles. Nor were they allowed to forget that they

were royally descended from the kings of France and England, and were

cousins to the mighty Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Vater’s overlord.

Their awareness of that must be reflected in everything they did.

As young Otho von Wylich stepped down, Anna’s heart almost

stopped. To her, this cousin by marriage, two years older than she,

seemed like a gift from God as he alighted on the cobbles. Oh, he

was fair to look at, with his wavy, unruly chestnut locks and his high

cheekbones, strong jaw, full lips and merry eyes, and he was charming

too as he greeted everyone, displaying the proper deference to his host

and hostess, with little of the gaucheness often seen in boys of his age.

When he rose from his bow to Anna, his smile was devastating.

She was already betrothed, as good as wed, and had been since the

age of eleven. When people addressed her formally, they called her

Madame la Marquise, for her future husband was Francis, Marquis of

Pont-à-Mousson, eldest son of Antoine, Duke of Lorraine. They had

never met – she had not even seen a portrait of him – and although she

was always being reminded of her great destiny, the prospect of marriage

still seemed unreal. Some of her dowry had already been paid, and she

had long expected her wedding to take place as soon as Francis reached

marriageable age at fourteen, this very year.

She had been too young for a betrothal ceremony: her consent had

been implicit in the contract her father had signed. She had accepted

without question the husband chosen for her, having been schooled in

her duty from infancy; but now, having seen Otho von Wylich, she

wished for the first time that she was not spoken for. She could not

drag her eyes away from Otho’s engaging smile.

As she struggled to hide the fact that her world had just shifted

seismically, Vater led the guests through the majestic Knight’s Hall, his

serious, craggy features becoming animated as he pointed out the

decorative sculptures to Otho.

‘This hall is said to have been built by Julius Caesar,’ he said proudly.

‘I well remember the great ceremonies that took place here,’ Tante

Elisabeth said.

Slowly, they processed through the state rooms. Anna was aware

only of Otho, standing just inches away, and of his eyes on her.

‘We had these apartments built on the model of the great French

chateaux on the Loire,’ Vater boasted, waving a beringed hand at the

fine furniture and tapestries. Anna saw her uncle and aunt exchange

envious glances. Mutter seemed serenely unaware. All this splendour

was no more than her due, for she had been a great heiress, and had

brought Vater rich territories and titles. She graced the court of Kleve

in a manner that was regal yet humble, as deferential as a woman should

be. Both she and Vater were strict in maintaining the elaborate code of

etiquette laid down by the dukes in the manner of their Burgundian

ancestors; in matters of courtesy and style, the court of Burgundy had

led fashionable Christendom for nearly a hundred years now. Mutter

and Vater also welcomed new ideas from the magnificent court of

France, not far to the west of Kleve, and from Italy, which permeated

north by means of visitors travelling up the Rhine. Anna sometimes

sensed that Vater’s court was too sophisticated and free-thinking for

Mutter’s taste; it seemed much more liberal than the court of Jülich had

been. But Mutter would never criticise what went on in Kleve.

When they reached the private apartments, wine was served,

the sparkling Elbling that Vater regularly had brought upriver from the

vineyards on the Mosel. Onkel Otho and Tante Elisabeth accepted their

goblets with alacrity. It was as well that it was not evening, for the rules

at court were strict, and all wine, even the Duke’s, was locked away at

nine o’clock by his Hofmeister, who took his duties very seriously.

As they sipped from their goblets of finest Venetian glass, the adults

talked, stiffly at first, then gradually relaxing, while their children sat

silently listening, Anna intensely aware of Otho, who was sitting beside

her.

‘Your father has a wondrous palace,’ he said.

‘I hope you will be able to see more of it,’ she replied. She felt sorry

for him, for he had no hope of inheriting any great houses, even though

it was no fault of his that he was a bastard. ‘But I am sure you live well

in Gennep.’

‘Not as well as you do here, Anna,’ he told her, with another of

those devastating smiles, and she thrilled to hear her name on his

tongue. ‘But I am fortunate. My father and stepmother treat me like

their lawful son. They have no other children, you see.’

‘But you have friends?’

‘Yes, and I have my studies, and an amiable tutor. One day, I will

have to make my own way in the world, probably in the Church.’

‘Oh, no!’ she exclaimed, before she could stop herself. ‘I mean, you

could surely have a happier life doing something else.’

He grinned. ‘You are thinking of the pleasures I would have to give

up,’ he said, making her blush. ‘Believe me, I think of them too. But I

have no inheritance, Anna. It will all go to a cousin when my father

dies. What else can I do?’

‘Vater will find you a post here, or Dr Olisleger, his chancellor, I am

sure!’

‘How kind you are, Anna,’ he murmured. Their eyes met, and she

read in his gaze all she could have hoped for. ‘I can think of nothing

I would like more than being at the court of Kleve. It would mean I

could see you more often.’

His words took her breath away. ‘Then I will ask for you,’ she

promised.

She noticed her mother watching them, a slight frown on her face.

Vater was warming to his favourite topic. She knew for a certainty that

she would hear the name Erasmus before too long. The great humanist

scholar was Vater’s hero, the man he admired above all others, and

whose advice he sought on religious matters.

‘Erasmus says the Church is not the Pope, the bishops and the

clergy,’ he declared. ‘It is the whole Christian people.’

Tante Elisabeth looked dubious, while Mutter’s expression remained

inscrutable. Anna knew Mutter did not agree with Vater on religious

matters. Devout as a nun, she was probably wincing inwardly to hear

the Holy Father in Rome dismissed as if he were of no importance.

‘Erasmus preaches universal peace and tolerance,’ Vater went on,

oblivious. ‘There can be no higher ideal than that. It inspires the way

I live my life, the way I govern my duchy and my court, and the way I

nurture my children.’

‘It is a high ideal,’ Onkel Otho observed, ‘but a dangerous one. Even

if he does not intend to, Erasmus encourages those who attack the

Church. It’s a short step from that to the heresies of Martin Luther.’

‘Luther speaks sense in many ways,’ Vater countered. ‘There are

abuses in the Church, and they need to be rectified.’

‘My lord has banned Luther’s works,’ Mutter said quickly.

‘I have indeed, twice,’ Vater confirmed. ‘But some of his protests

against the Church are justified. No one should have to pay priests to

forgive their sins and save them from Purgatory, and it’s wrong that the

princes of the Church live in luxury when our Lord was a simple

carpenter. But to deny five of the sacraments is plain heresy.’

‘Your son-in-law would not agree with you,’ Onkel Otho replied.

‘The Elector of Saxony has extreme views,’ Vater said, looking

pained, ‘and I fear Sybilla has become infected with them, for a wife

is bound to follow her husband. The Elector wants me to join his

Schmalkaldic League of German Lutheran princes, but I will never do

that.’

‘Yet you allied yourself to him by marriage,’ Onkel Otho persisted.

‘You are linked to the League whether you like it or not.’ Now it was

Mutter’s turn to look pained. It must have gone against all her beliefs to

see her daughter given to a Protestant.

It seemed an argument was stirring, but just then, the bell at the top

of the Johannisturm in the inner courtyard chimed four o’clock, and

Mutter seized her opportunity. Anna guessed she did not want her

offspring hearing any more talk against the Church and the true faith in

which she had nurtured them.

‘Children,’ she said brightly, ‘why don’t you show your cousin Otho

around the rest of the castle?’

The young people all jumped to their feet, Anna secretly rejoicing.

‘It will be our pleasure,’ thirteen-year-old Wilhelm said earnestly.

Anna knew Otho would soon be receiving a lecture on the architecture

of the Schwanenburg and the glorious history of Kleve – and she was

right. As they returned through the state apartments, Wilhelm, who

had all the virtues save a sense of humour, humility and empathy with

others, started waxing forth on how he had been born here in the

Schwanenburg and how rich and prosperous the duchy was.

‘Our father is called Johann the Peaceful, because he rules so wisely,’

he boasted. ‘When he married our mother, she brought him Jülich and

Berg, and lands stretching for four thousand miles. When I am duke of

Kleve, I will inherit all that, and I will be as wise as my father.’

Anna saw Otho smothering a smile.

‘Otho did not come to hear all this, Bruder,’ she said. ‘It’s a beautiful

day, and you’ve been excused lessons for the afternoon.’ She

turned to Otho, and felt herself grow hot. ‘Would you like to go up the

Schwanenturm? The views are wonderful, and I can tell you all about

the legend of Lohengrin.’

‘It’s too warm to climb all those stairs,’ Emily protested, her rosebud

lips pursed in a pout.

‘Emily, you are such a lazybones,’ Anna sighed.

‘But I should love to see the views,’ Otho said, his twinkling eyes

still on Anna, ‘and the exercise will be good for us.’

‘I think Otho would prefer to see the Spiegelturm,’ Wilhelm said, as

if Otho had not spoken. ‘The ducal archives are most interesting.’

‘Oh, Wilhelm, it’s always what you want!’ Emily cried.

‘You can take Otho there afterwards,’ Anna said firmly. ‘But first, he

wants to see the Schwanenturm.’

‘Then you take him,’ Wilhelm ordered. ‘I will go and look out some

things I want to show him.’

‘I’m coming with you,’ Emily said. ‘I can help find them.’

‘You’re just too lazy to climb the stairs,’ Wilhelm scoffed, looking

none too pleased at the prospect of his twelve-year-old sister’s company.

‘Come,’ Anna said to Otho. ‘Let’s leave them to their squabbles.’

She led him away before Wilhelm could stop her. She had never known

such luck. Her life was hemmed around with rules, ritual, sewing and

her mother’s endless vigilance, and the chance of a short time alone

with this most handsome youth was beyond her wildest imaginings; it

was incredible that it had been afforded her so easily, without any effort

on her part. It was an escapade of which Mutter might well have

disapproved, for she had always enjoined that a young lady should never

be alone with a man, lest her reputation be compromised. She had

never explained exactly how that might happen, though it was clearly a

dreadful thing. But Otho did not count, surely? He was family, and he

was not much older than Anna.

The mighty Schwanenturm loomed above them, its square shadow

falling on the cobbled courtyard. Anna was headily aware of Otho

walking just a pace behind her. She was glad she had donned her new

red silk gown with its gold bodice embroidered with loops of pearls.

She felt beautiful wearing such a dress, with her fair hair loose down her

back. Sybilla, whose portrait showed off the slanting eyes and long

golden tresses that had captivated the Elector, was the beauty of the

family, everyone was agreed on that; but Anna revelled in the thought

that she too could look pleasing.

The guards on duty at the door stood to attention as they approached.

‘My ancestor, Duke Adolf, built this tower,’ Anna said, pushing

open the heavy door.

‘Allow me,’ Otho said, taking its weight. Anna went ahead, lifting

up her gorgeous skirt to ascend the stairs.

‘The old tower fell down about a hundred years ago,’ she went on,

trying to conceal her nervousness behind a barrage of facts. ‘Duke Adolf

rebuilt it much bigger than before.’

‘It’s certainly high!’ Otho said. ‘These steps go on for ever. Shall we

rest for a moment?’

Anna turned on the stairs to see him looking up admiringly at her.

‘You are very pretty,’ he said, ‘and that gown becomes you so well.’

His eyes travelled up appreciatively from her slender waist to the swell

of her breasts beneath the velvet bodice.

Thrilled by his praise, she smiled down at him. She could not help

herself. She knew she should not be allowing him to say such familiar

things to her, or herself to acknowledge them. Yet she was bursting

with such joy that she had no will to walk away, or to spoil the moment.

They were slightly breathless by the time they ascended the final

flight of stairs leading to the turret at the top of the tower and entered

a narrow, sparsely furnished room with windows at each end. The

Turkey carpet must have cost a fortune in its day, but it was now

threadbare.

Anna crossed to the window overlooking the river. Below,

the town of Kleve lay spread out before her, a patchwork of red roofs

and spires.

Otho stood right behind her.

‘It is a fair sight,’ he said, looking over her shoulder. She could feel

his breath on her ear. ‘So tell me about Lohengrin.’ His voice was like a

caress.

Anna tried to focus on the legend she had promised to recount, but

her mind was too overwhelmed by this strange, heady feeling. Was this

love? She had seen how deeply her parents loved each other, and had

learned, from listening to the ladies and maids gossiping, that love

could also be a kind of madness that made people act like fools, as

if they were out of their senses. It could make you ecstatically happy

or desperately sad. And now, standing in this dusty little room,

alone with a young man for the first time, she understood what it was

to be powerfully attracted to someone. It was a glorious feeling, and

frightening too, as if she were being impelled towards something

momentous and dangerous, and had not the mastery to stop herself.

But she must! She would soon be a married woman, and had been

schooled in absolute loyalty to her husband-to-be.

‘Do you know why this is called the Swan Tower?’ she asked Otho,

forcing herself to collect her thoughts and speak. ‘I don’t suppose you

hear much about the legends of Kleve in Limburg.’

‘My mother used to tell me stories when I was little,’ he answered,

‘but I have forgotten them mostly.’

‘Above us, on top of the turret, there is a golden weathervane,’ Anna

said, a touch breathlessly. ‘It bears the swan that the old counts of

Kleve blazoned on their coats of arms, in honour of the Knight of the

Swan, the mysterious Lohengrin. See here.’ She turned and drew from

her bodice an enamelled pendant. ‘This is my personal device. The

two white swans stand for innocence and purity.’ Otho cradled her

hand in his as he bent to look in her palm. Suddenly, he kissed her

lightly on the wrist. It gave her the most pleasurable jolt.

She was not quite mad – not yet. She had been taught that no

virtuous woman would let a man kiss her until he made her his affianced

bride. She withdrew her hand, and Otho straightened up.

Her voice shook a little as she continued her story. ‘Lohengrin’s boat

was guided by two white swans when he sailed along the Rhine long

ago to visit a countess of Kleve named Elsa. She was in deep distress

because her husband had died and a tyrant was trying to usurp his place

by forcing her to wed him. Lohengrin came to her aid. He overthrew

the tyrant and married her.’

Otho’s eyes were shining into hers. ‘If she was as beauteous as

another princess of Kleve I could mention – then I take my cap off

to Lohengrin.’ His voice sounded a little hoarse.

Anna’s cheeks suddenly felt very hot. She had no idea how to

respond to such a compliment.

‘He was a renowned hero,’ she said, struggling to act normally. ‘But

on the day after their wedding, he made Elsa promise never to ask his

name or his ancestry. Unknown to her, and to all, he was a knight of

the Holy Grail and was often sent on secret missions. She agreed, and

they lived very happily together, and had three fine sons. They were my

ancestors.’

‘You are going to tell me that it all went wrong,’ Otho said.

‘It did. Elsa was desperate to know if her sons would have a great

inheritance from their father. She could not contain herself, and asked

him the question she had sworn never to ask. When she did, Lohengrin

fell into anguish. He tore himself from her arms and left the castle –

this very castle. And there, on the river, waiting for him, were the two

swans with the boat that had brought him to Kleve. He sailed away in

it, and was never seen again.’

Otho was shaking his head, his eyes holding hers. ‘And what

happened to Elsa?’

‘She was so overcome with grief for her loss that she died. She had

loved Lohengrin so much.’

For the first time, it was dawning on Anna how terrible Elsa’s loss

had been. That sad realisation must have been plain on her face, for,

without preamble, Otho stepped forward and folded his arms around

her, drawing her close to him. Before she could stop him, he had pressed

his lips to hers and touched her tongue with his. It was the strangest

thing, at once wonderful and repulsive. She had never dreamed that

kissing could be like that, but she knew it was wrong to be doing it.

What would her parents think of her?

‘No,’ she said, pulling back.

He held her fast in his embrace. ‘Yes!’ he breathed. ‘Please don’t

deny us this pleasure! It can do no harm. You need not fear it.’

‘I might have a baby,’ she protested, and was surprised when he

laughed. ‘I might,’ she warned. ‘Mother Lowe told me kissing leads to

babies.’

‘And who is Mother Lowe?’ he asked, nuzzling her nose with his as

she struggled half-heartedly to free herself.

‘She is my nurse.’

‘Little she knows! You can’t get a baby from kissing. It’s harmless.

And you were enjoying it, I could tell.’ He was still holding her tight,

grinning at her so engagingly that she felt her knees melt. It was

thrilling, talking about such things with a man.

He kissed her again, gently, tenderly this time, and then he was

drawing her down on to the carpet, kissing her eyes and stroking her

cheeks. His hands strayed elsewhere, and the glorious sensations he was

awakening in her drowned out the alarums ringing in her head. He had

said there was nothing to fear, and she believed him. He was a guest in

her father’s house – a well-brought-up young man who, she could count

on it, knew how to behave. And there was a rising, breathless excitement

in him that she found infectious.

‘Oh, Anna!’ he murmured, his eyes on hers as he twined her hair

around his fingers, his breathing becoming more rapid and tremulous.

‘Let me love you! I will not hurt you.’ His lips closed on hers again,

with greater fervour, and then he reached down, pulled her beautiful

silk skirts and chemise aside and – to her astonishment – began gently

touching her private parts. She did not resist him: she was too far

immersed in feelings and sensations she had never dreamed of.

‘As you have lips here,’ he whispered, caressing her mouth with his

tongue, ‘so you have them here, for the same purpose.’ His fingertips

moved rhythmically, exploring more boldly, and Anna felt the most

exquisite pleasure mounting within her. There was no shock, just

surprise at how little she had understood her own body – and no shame.

Here it was, the madness of which the women had spoken! Had she

lived until now?

What followed was utterly glorious, and she gave herself up to it

without further thought, being incapable of reason. A little pain – and

then she was ascending to Heaven. As the pleasure mounted, she felt

Otho’s body spasm. He cried out, and then, as he slowly relaxed on top

of her, and inside her, holding her tightly and murmuring incoherent

words of love, she was overcome by a wave of unstoppable ecstasy,

building and building until she thought she would pass out.

She lay there stunned as he turned his head to face her, and smiled.

‘Did you enjoy our kissing, Anna?’

She nodded, thinking how beautiful his eyes were.

‘Oh, sweet Anna,’ Otho murmured, his lips on hers, ‘you loved it,

didn’t you? I could tell.’

‘Yes,’ she breathed. ‘I never dreamed there could be pleasure like

that.’ She lay there in his arms, feeling blissful, wanting to prolong the

moment for as long as possible.

‘This is what God intended for men and women!’ he smiled.

‘It wasn’t wrong, was it?’ Her sense of fitness was returning, and

with it the awareness that she had been a party to something forbidden.

‘Of course not.’ He released her and sat up, lacing his hose. ‘But let’s

keep it as our secret. Our parents wouldn’t understand. They think such

pleasures should be kept for marriage, but I see no harm in enjoying

them before.’

Anna began to feel guilty. Carried away on a tide of madness, she

had betrayed the precepts drummed into her by her mother. But it had

been so beautiful! Why, then, did she feel a creeping sense of dread? It

was the fear of being found out, she realised; that was all. How could

she regret something that had brought her such joy?

‘Can we be married, Anna?’ Otho asked, gazing at her longingly.

‘Oh, I do wish that!’ she cried. ‘But I am promised to the Duke of

Lorraine’s son.’ Her voice caught in her throat.

He stared at her. ‘I did not know.’

She shook her head. ‘It is not what I want, but my father is set on an

alliance with Lorraine.’ Belatedly, she realised that what she had done

with Otho was meant to be saved for marriage; they had stolen what

rightfully belonged to Francis.

‘Betrothals can be broken,’ Otho said.

Anna shook her head. ‘I doubt it.’ She felt tears welling, and knew

her misery must be written plain on her face.

She stood up, tidied herself and moved towards the door.

‘Where are you going, Liebling?’ Otho asked, looking bewildered.

‘We should go back. We have been here too long,’ she said.

He pulled her into his arms and kissed her again, long and yearningly,

leaving her in no doubt as to his feelings. They belonged to each other

now, and nothing could change that: it was what his lips were saying to

her. She was drowning in emotion. She wanted the moment to go on

for ever, but made herself break away. She dared not stay alone with

him here any longer.

‘I love you, Anna,’ she heard him whisper.

Ignoring the soreness between her legs, she hastened down the stairs,

bereft, and desperate to cry out her sorrow in her chamber, where there

would be clean water, soap and towels to remove all trace of her

sinfulness, and she could take off the gown of which she had been so

proud, but which now bore the stains of her fall from grace. Otho was

right. What had passed between them must remain a secret; besides,

Anna did not have the words to describe what had happened. If her

parents found out, she would be blamed. She should not have been

alone with Otho in the first place, let alone allowed him to kiss her and

lie with her. They would say he had dishonoured her, a princess of

Kleve, when he was a guest in her father’s house. Yet it had not been

like that! She had lain with him willingly – and she had been in ecstasy.

Otho had said he loved her and had spoken of marriage – yet they could

never belong to each other. Tears welled again in her eyes as she emerged

from the tower. She prayed the guards would not notice her distress.

‘Anna?’ Otho cried, behind her. ‘Are you all right?’

‘The Spiegelturm is over there,’ she called back, her voice catching.

‘They’ll be waiting for you. Tell them . . . tell them my head is aching

and that I’ve gone to lie down.’

Leaving him standing there, she hastened away to her chamber.

Mercifully, it was deserted. Mother Lowe was enjoying her usual

afternoon nap.

Crying, Anna unlaced her bodice and sleeves and let her gown fall to

the floor, then poured some water from the ewer into the bowl beside

it. It was while she was scrubbing herself that she noticed blood on her

lawn chemise. Was this the monthly visitation Mutter had warned

her about? When Anna had asked why women had to bleed, Mutter

had simply said that it was God’s will, and that Anna would learn more

about it when she was about to be married. Anna wondered if it had

anything to do with what she had done this day.

She changed her chemise and put the soiled one to soak in the bowl

of water. What to do about the dress? There was blood on the lining of

that too, so she took the damp cloth she had used to wash herself and

rubbed it away. Soon, the stain was nearly gone; if you were not looking

for it, you would not see it. She laid the damp dress away in the chest,

and put on another, of creamy silk banded with crimson. Then she

stared at herself in the mirror, checking that no one could see she had

been crying. Her eyes looked a bit red, but she could put that down to

the headache. And it was true, her head was aching, from the burden of

love, guilt and desperation she now carried.

When the bell in the tower summoned everyone to supper, she sped

down the stairs and arrived in the dining chamber on time. Vater never

could abide unpunctuality.

Otho was there already, with Onkel Otho and Tante Elisabeth. She

wanted to fly into his arms, but made herself avoid his eyes, aware that

he was avidly seeking hers. No one must guess the secret that lay

between them.

‘Is your head better, my dear?’ Tante Elisabeth asked her.

‘I am much better, thank you,’ Anna told her.

‘You’ve changed your dress, child,’ Mutter observed.

‘I was too hot in the other one.’ She was praying Otho would not

give them away, by some chance word or glance. Mutter could be

sharply observant.

The meal was an ordeal, and she struggled to behave normally, and

to eat the choice carp and roasted pork served to her. She dared not

think of what had happened earlier, lest her face flame and betray her.

It wasn’t easy, with Otho sitting so dangerously near to her, looking so

handsome, and her stomach churning with love and desire. It took all

her inner resources to behave as usual. She did not think anyone noticed

anything amiss.

After supper, the Duke’s consort of musicians arrived with their

trumpets, lutes and harps. Mutter would always have harp music if she

could; it was her favourite, and she bestowed one of her rare smiles on

the players when the last note had been struck.

‘I wish we could dance,’ Emily said wistfully, ‘or sing.’

Mutter frowned. ‘My dear child, you know it is immodest for a

woman to dance or sing in public.’

‘I know,’ muttered Emily gloomily, ‘but I do so love music and

dancing.’

Tante Elisabeth regarded her with disapproval.

‘She inherited her love of music from me,’ Mutter said. Elisabeth

gave a thin smile.

The men were talking of politics.

‘The Emperor has ambitions. He wants the duchy of Guelders for

himself,’ Vater was saying. ‘But it will go to Anna’s betrothed.’ Anna

saw Otho’s expression darken, but Vater continued, unheeding. ‘Duke

Charles is childless, and Francis, as his great-nephew, will inherit. I

myself have a claim to Guelders, but I relinquished it as part of the

terms of the betrothal contract; I am content that my daughter will be

duchess of Guelders.’

Anna struggled to maintain her composure. She most certainly

was not content at the prospect. Her imaginary image of Francis had

metamorphosed from a courteous, smiling boy into a disapproving,

suspicious man.

‘The Emperor also has a claim to Guelders, does he not?’ Onkel

Otho asked.

‘Yes, through his mother,’ Vater told him. ‘But if he presses it, we

will be ready for him. Kleve may be part of the Holy Roman Empire,

but it is also one of the leading principalities of Germany. We will not

let the Emperor dictate to us. We protect our independence. We have

our own courts and our own army, and I keep control of our foreign

policy.’ Wilhelm was listening avidly.

‘But Charles is very powerful. You would have a fight on your

hands,’ Onkel Otho said.

‘Ah, but he might well be going to war with England, if King Henry

continues in his attempt to divorce his Imperial Majesty’s Aunt

Katherine to marry a courtesan. I count on Charles being too preoccupied

with that, and with the Turks encroaching on his eastern

borders, to concern himself with Guelders. I have the means to raise a

mighty army.’ The Duke paused as a servant refilled his goblet. ‘I met

King Henry of England once, you know. Eight years ago, I visited his

kingdom in the train of the Emperor.’

‘What was he like, Vater?’ Wilhelm asked.

‘Handsome. Bombastic. Full of his new title. The Pope had just

named him Defender of the Faith for writing a book against Martin

Luther.’

The conversation dragged on interminably. There had been no

chance of any conversation with Otho, as Wilhelm and Emily were

sitting between him and Anna, and now, at precisely nine o’clock, the

Hofmeister was arriving to remove the wine, signalling that it was time

to retire. It was forbidden to the courtiers to sit up any later, playing

cards, drinking or even just chatting, and Vater liked to set a good

example.

Everyone bade each other a good night. As Anna was leaving the

room, she felt a hand close on hers from behind, pressing something

into her palm. She swung round, to see Otho giving her a longing look.

Fortunately, no one seemed to have noticed, and she walked on, out of

the dining chamber, to receive her parents’ blessings and hasten up to

her room.

Only then did she open her hand. She was holding a tiny package

wrapped in a scrap of damask; inside was a ring enamelled in red. There

was a note, too. ‘Sweet Anna, please accept this token of my esteem.

My family’s coat of arms has a red ring, so it is special to me. I hope

you will wear it and think kindly of your servant.’

He had given her his special ring! If only it could have been her

betrothal ring! And yet, even though it was not, it still symbolised

eternal love.

She dared not keep the note; though it broke her heart to do it,

she tore it into tiny pieces and threw them out of the window. But

the ring she hid under the loose floorboard in the corner of her bedchamber.

The Wicked Wife is an e-short and companion piece to Katheryn Howard: The Tainted Queen, the captivating fifth novel in the Six Tudor Queens series by bestselling historian Alison Weir.

1525. As Anne Boleyn’s star rises at Henry VIII’s court, Jane Parker’s marriage to Anne’s brother, George, brings her status and influence. But theirs is not a happy union and results in a bitter and bloody end.

1540. When Katheryn Howard, a young cousin of the Boleyns, becomes the King’s fifth bride, Jane’s past allegiance to the crown secures her senior rank in the new queen’s household.

But memories of her own ill-fated marriage stir Jane’s sympathies towards Katheryn and her secret liaison with a young man at court. Jane’s collusion places both women at tremendous risk, while the fate of Anne Boleyn weighs heavily on their minds. They must decide where their loyalties truly lie, before it’s too late…

The Princess of Scotland is an e-short and companion piece to Katheryn Howard: The Tainted Queen, the compelling fifth novel in the Six Tudor Queens series by bestselling author and historian Alison Weir.

‘The King would not approve of my falling in love … My marriage was in his gift’

Brought up in the magnificent castles of Scotland under the storm of her parent’s turbulent marriage, Margaret Douglas is well-acquainted with the changing whims of those who hold power. And when her father is exiled by King James V, Margaret is sent to England to seek refuge with her uncle, King Henry VIII.

Margaret is an asset to Henry, who plans to use her eligible marriage status for his own advantage. But, surrounded by the excitement and indulgences of the English court, will Margaret be able to resist the temptations of a young admirer? As she well knows, keeping secrets from the King can be a dangerous game…

The King’s Painter by bestselling historian Alison Weir is an e-short and companion piece to the captivating fourth novel in the Six Tudor Queens series, Anna of Kleve: Queen of Secrets.

‘There are certain matters that are better handled by ladies than by ministers or ambassadors’

King Henry VIII is set to marry a woman he’s never met. Wary of rumours whispered by foreign envoys, he sends Susanna Gilman, royal painter and trusted friend, to Kleve to find out more about his chosen bride.

Before long, Susanna is returning to England with the Princess Anna, assuring the King she is a suitable match. But the King is disappointed – Anna is not as beautiful as her portrait.

Susanna is called upon once again to use her position as confidante to the new Queen to find out more about her past, and free the King from his marriage. But will she be able to put her blossoming friendship with Anna to one side to fulfil her duty to the King?

Each sunset, as I go to the chapel, I find myself looking for her. I look for details. What she is wearing, some clue to her identity. But she fades away if I look at her directly. I can just glimpse the blur of a hood, or a widow’s wimple, and those sad eyes, staring at something – or someone – I cannot see.

Anne Basset served four of Henry VIII’s queens, yet the King himself once pledged to serve her. Had fate not decreed otherwise, she might have been his wife – and Queen of England.

But now, far from court and heavy with her husband’s child, Anne prays in the Hungerford chapel, and awaits the ghostly figure she knows will come. This is her story, one that entwines with the fate of another Lady Hungerford from not so many years before. They say there’s a curse on this family…

Featuring the first chapter of Anna of Kleve: Queen of Secrets.

I was to be chief mourner – I, for whom Queen Jane had done more than anyone. She could never have filled the shoes of my dear, sainted mother – no one could – but she had done her very best to restore me to my rightful place in my father’s affections, and for that I shall always be grateful.

Henry VIII’s third queen is dead, leaving the King’s only son without a mother and the country without a queen. And as preparations are being made for Queen Jane’s funeral, her stepdaughter, the Lady Mary, laments the country’s loss.

But, only a month later, the King has begun his search for a new wife. Will Mary accept this new queen, or will she be forced to live in the shadows of Queen Katherine, Queen Anne Boleyn and Queen Jane for ever?

A spellbinding companion piece to Jane Seymour: The Haunted Queen, featuring the first chapter of the novel.

The Grandmother’s Tale by historian Alison Weir is an e-short and companion piece to the spellbinding third novel in the Six Tudor Queens series, Jane Seymour: The Haunted Queen

SIX TUDOR QUEENS. SIX NOVELS. SIX YEARS.

The Chateau of Briis: A Lesson in Love by historian Alison Weir is an e-short and companion piece to the Sunday Times bestseller Anne Boleyn: A King’s Obsession, the second novel in the spellbinding series about Henry VIII’s queens.

‘May I have the pleasure of your hand in the dance, mademoiselle?’

1515 – Dressed in wine-coloured satin, with her dark hair worn loose, a young Anne Boleyn attends a great ball at the French court. The palace is exquisitely decorated for the occasion, and the hall is full with lords and ladies – the dancing has begun. Anne adores watching the game of courtly love play out before her eyes, though she is not expecting to be thrown into it herself. But moments later, a charming young man named Philippe du Moulin approaches to ask for her hand in the dance. And before she can resist, so begins Anne’s first lesson in love.

The Tower is Full of Ghosts Today is an e-short and companion piece to the Sunday Times bestseller Anne Boleyn: A King’s Obsession, the second novel in the spellbinding series about Henry VIII’s queens.

Jo, historian and long-term admirer of Anne Boleyn, takes a group on a guided tour of the Tower of London, to walk in the shoes of her Tudor heroine. But as she becomes enthralled by the historical accuracy of her tour guide and the dramatic setting that she has come to love, something spectral is lurking in the shadows . . .

The Blackened Heart by foremost and beloved historian Alison Weir is an e-short and companion piece that bridges the first two novels in the Six Tudor Queens series, Katherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn. Fans of Philippa Gregory and Elizabeth Chadwick will delight in this mysterious tale, drawn together from fragments of history – and a good dose of speculation. Or is it…?

Margery Otwell, a self-made gentleman’s young daughter, gets her first taste of courtly life when she takes up a position as chamberer to Lady Peche of Lullingstone Castle. Dances, music, feasting – and a seduction – follow, and Margery learns the rules of courtly love the hard way.

Saved from disgrace by the kindly Sir John Peche, Margery finds herself at court waiting on Queen Katherine. Little does Margery know that she is already a pawn in a game of power, irrevocably bound to the fall of the lady she will come to love as her mistress, Queen and friend.

Six Tudor Queens: Writing a New Story is an introduction to the Six Tudor Queens series by eminent historian Alison Weir. The lives of Henry VIII’s queens make for dramatic stories that will offer insights into the real lives of the six wives based on extensive research and new theories that will captivate fans of Philippa Gregory and readers who lost their hearts (but not their heads) to the majestic world of Wolf Hall.

In all the romancing, has anyone regarded the evidence that Anne Boleyn did not love Henry VIII? Or that Prince Arthur, Katherine of Aragon’s first husband, who is said to have loved her in fact cared so little for her that he willed his personal effects to his sister? Or that Henry VIII, an over-protected child and teenager, was prudish when it came to sex? That Jane Seymour, usually portrayed as Henry’s one true love, had the makings of a matriarch? There is much to reveal …

Read extractThe idea of writing a series of six novels about the wives of Henry VIII came suddenly to me as I was discussing another proposal with my agent. It was an obvious choice, for I have studied Henry’s queens over several decades, and published books on them, notably a collective biography in 1991, which I am now re-researching and rewriting.

The lives of the six wives make for dramatic stories. The extensive research I have done has afforded new insights into their lives. In all the romancing, for example, has anyone noticed the evidence that tells us what Anne Boleyn felt about being pursued by Henry VIII? Or that Henry VIII, an overprotected teenager, was prudish when it came to sex? I could go on…

I want to seek out the truths that lie behind the historical evidence and, for this, fiction is a versatile medium because it offers scope to develop ideas that have no place in a history book, but which can help to illuminate the lives of these queens. A historian uses such inventiveness at her peril – but a novelist has the power to get inside her heroine’s head, which can afford insights that would not be permissible to a historian, yet can have a legitimate value of their own – although I believe that the fictionalised version must be compatible with what is known about the subject.

Arthur: Prince of the Roses by bestselling historian Alison Weir is an e-short and companion piece to her stunning novel, Katherine of Aragon, the first in a spellbinding six-novel series about Henry VIII’s Queens. Fans of Philippa Gregory and Elizabeth Chadwick will love this insight into the story of this illfated Tudor prince.

‘You are the first prince of my line, the Tudor line.’

Arthur, the first Tudor prince, is raised to believe that he will inherit a kingdom destined to be his through an ancient royal bloodline. He is the second Arthur, named for the legendary hero-king of Camelot.

To be a worthy ruler, he must excel at everything – and show no weakness. But Arthur is not strong, and the hopes of England weigh heavy on his slight shoulders. And, all the while, his little brother Harry, the favoured, golden son, is waiting in the wings.

Alison Weir is the top-selling female historian (and the fifth best-selling historian overall) in the United Kingdom, and has sold over 2.7 million books worldwide. She has published seventeen history books, including The Six Wives of Henry VIII, The Princes in the Tower, Elizabeth the Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry VIII: King and Court, Katherine Swynford, The Lady in the Tower and Elizabeth of York. Alison has also published five historical novels, including Innocent Traitor and The Lady Elizabeth. Her latest biography is The Lost Tudor Princess, about Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox. She is soon to publish Katherine of Aragon: The True Queen, the first in a series of novels about the wives of Henry VIII. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and Sciences and an Honorary Life Patron of Historic Royal Palaces, and is married with two adult children.

Alison Weir is the top-selling female historian in the United Kingdom, and has sold over 2.7 million books worldwide. She has published seventeen history books, including Elizabeth the Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, The Lady in the Tower and Elizabeth of York, and five historical novels. Her latest biography is The Lost Tudor Princess. She is soon to publish Katherine of Aragon: The True Queen, the first in a series of novels about the wives of Henry VIII.